Bereshit Rabbah 76:2

R. Yehudah said in the name of R. Ilai: Aren’t fear and being scared the same thing? (I feel “being scared” is the best translation for “vayezter lo” rather than something like “And he was anxious.”) Rather (they refer to two different things), “And he was afraid”-- referred to him being afraid that he would kill, and “he was scared” that he would be killed.

He said, “If he is stronger than I am, then he will kill me. And if I am stronger than him, I will kill him. That is why it says, “And he was afraid”-- that he would have to kill. And “he was scared” that he would be killed.

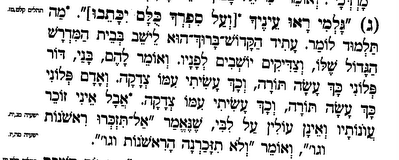

Footnote:

(The footnote seeks to explain why Mirkin has pointed it the way that he did—why point the first verb as yaharog “to kill” and the second as yayhareg “to be killed”? What is at stake is what gets the “me-od” which indicates that which Ya’akov was more afraid of—killing or being killed? From the manuscript that he is using, I assume there are no hints to guide him—both verbs are spelled yud hay reish gimel.)

Translation of the footnote: Aren’t fear and “being scared” the same thing? So why does it say “he was afraid” and “he was scared?” Rather there are two matters here. First he was worried that he would have to kill Esav. And second he was scared about himself that he would be killed. But wouldn’t it be more fitting to connect “and he was fearful” that he would be killed and “he was scared” to “that he would have to kill”? (implying that the me-od should be attached to his worry that he would be killed—the thing he should be more scared of) Rather, maybe this is the way of the thoughts of a hero who goes out to war, that at first he sees himself being able to kill his enemy, but then after, he sees the worry in his heart that maybe the opposite will happen to him.

And maybe R. Yehudah in the name of R. Ilai was seeing it as a pious person would as he was a righteous person as it says in “B”K 103a” “It once happened with a certain pious man… (and that righteous person was either R. Yehudah or R. Ilai)” (A righteous person would think : ) The killing of another is more difficult than killing oneself.

In defense of this intepretation the Mirkin cites the Albeck and Yalkut Shemoni. In the Theodore “And he was fearful that he would have to kill and he was scared that he would be killed.” (The J. Theodore and C. Albeck edition have an extra yud in the first verb “vayira she lo yAyhareg (spelled with two yuds)” implying that the second verb must be “yaharog.”) And in the Yalkut “And he was fearful that he would have to kill and he was scared that he would be killed.—(The second verb is spelled with a vuv, forcing it to be read vayaharog and the second verb must conversely be read yayhareg.)

(Mirkin then offers the parallel for “If he is stronger that me, he will kill me…” in the Theodore/Albeck.)

“If he is stronger that I am”—in the Theodore: “If he is stronger that I, will he not kill me?!, and if I am stronger that him, will not kill him?!,”( in the language of surprise). And see what is there (Ayen mah yesh).

(One question is: Doesn’t this last part undo the suggestion that the first statement referred to worrying that he would “have to kill” and the second that he would “be killed?” For it clearly states that his first thought is that Esav might be stronger than he is and he would be killed-- in both the Margulies and the Theodore.)

In fact, in the end, in the Theodore/Albeck, the ayen mah yesh is that it inverts the two so that he is very fearful that he will be killed and he is scared that he will kill.

But the Mirkin retains the suggestion that he is more afraid to kill than he is to be killed.